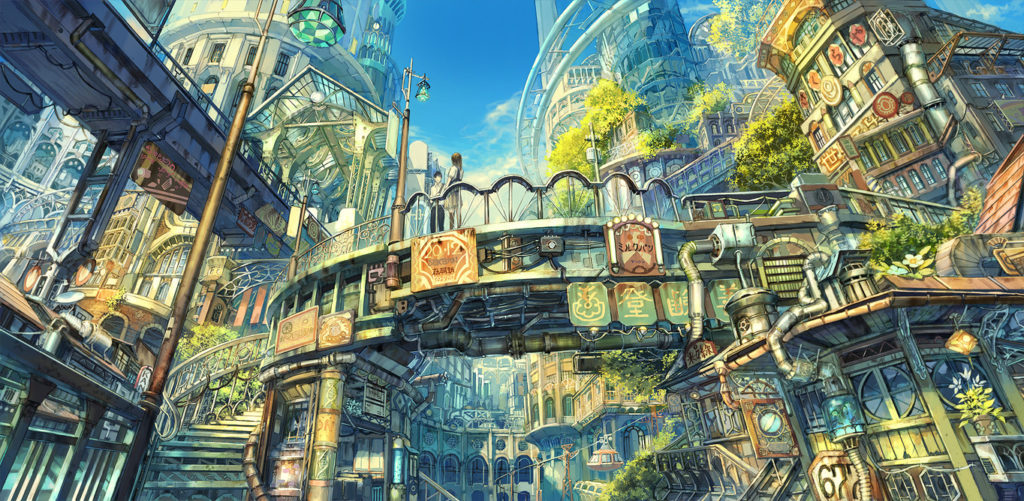

Munashichi, Future Economic View of Innocence, 2015

Literary subgenres morph at incredible speeds. The reasons why are embedded in a complex web of social, political, psychological, literary, technological, and pop-cultural forces. The genre of Fantasy is a good example of an ever-expanding universe of subgenres which intersect, coalesce, and transmutate into wildly different forms — from Fantasy, to High Fantasy, to Epic Fantasy, Grimdark to Noblebright Fantasy, to Alternate Universe Fantasy, to Sci-Fi Fantasy, to Urban Fantasy, to Paranormal Fantasy. The list is long and open-ended.

Perhaps it’s our penchant for cataloging and quantifying everything. So stories that were once simply labeled Romance are now sifted down to particular elemental components (Historical Romance, Contemporary Romance, Romantic Suspense, Erotic Romance, Romantic Comedy, Paranormal Romance, Gay Romance, Multicultural Romance, etc., etc.). Whatever the forces behind such atomization, one of the underlying components that drives the formation of many subgenres is worldview — how the reader/writer sees, or wants to see, the world.

In the case of Solarpunk, one of the latest genre iterations, an optimistic eco-centric humanism is the driving worldview behind the speculative world.

TV Tropes defines Solarpunk in this way:

Solarpunk is a genre of Speculative Fiction that focuses on craftsmanship, community, and technology powered by renewable energy, wrapped up in a coating of Art Nouveaublended with African and Asian aesthetics. It envisions a free and egalitarian world with a slight bend toward social anarchism. Standing as both a reaction to the nihilism of Cyber Punk and a solution to a lot of the problems we face in the world, Solar punk works look toward a brighter future (“solar”) while deliberately subverting the systems that keep that brighter future from happening (“punk”).

At the site Solarpunk Anarchist, this definition is considerably developed:

Solarpunk is a (mostly) aesthetic-cultural and (sometimes) ethical-political tendency which attempts to negate the dominant idea which grips popular consciousness: that the future must be grim, or at least grim for the mass of people and nonhuman forms of life on the planet. Looking at the millennia-old rift between human society and the natural world, it sets as its ethical foundation the necessity of mending this rift, transforming our relation to the planet by transcending those social structures which lead to systemic ecocide.

It draws a lot from the philosophy of social ecology, which also focused on mending this rift by restructuring society to function more like ecology: non-hierarchical, cooperative, diverse, and seeking balance.

Solarpunk’s vision is of an ecological society beyond war, domination, and artificial scarcity; where everything is powered by green energy and a culture of hierarchy and exclusion has been replaced by a culture founded on radical inclusiveness, unity-in-diversity, free cooperation, participatory democracy, and personal self-realisation.This would be a world of decentralised eco-cities, 3D printing, vertical farms, solar glass windows, wild or inventive forms of dress and design, and a vibrant cosmopolitan aesthetic; where technology is no longer used to exploit the natural world, but to automate away needless human labour and to help restore the damage the Oil Age has already done. Solarpunk desires societies of polycultural ethnic diversity and gender liberation, where each person is able to actualise themselves in societal environment of free experimentation and communal caring; and driven by an overriding ethos of compassionate rationalism, where science and reason are not seen as antithetical to imagination and spirituality, but as concepts which bring out the best in each other.

While other describe Solarpunk simply as science fiction that is not “depressing,” the genre apparently leans into more than just an upbeat vibe. There is also an “ethical-political tendency” to “negate [a] dominant idea” and “transcend[] those social structures which lead to systemic ecocide.” Whereas eco-fiction (which includes the more recent climate fiction) tends to frame more dystopian, apocalyptic warnings to the genre message, Solarpunk chooses a more humanistic approach. Or as the TV Tropes definition puts it, “Solar punk works look toward a brighter future.”

In this sense, the genre is much more than simply “entertainment.” Rather, it is a visionary movement of a hopeful future. For example, the Solarpunk Anarchist page on Facebook recently linked to the article entitled Solarpunk wants to save the world.

Solarpunk is the first creative movement consciously and positively responding to the Anthropocene. When no place on Earth is free from humanity’s hedonism, Solarpunk proposes that humans can learn to live in harmony with the planet once again.

Solarpunk is a literary movement, a hashtag, a flag, and a statement of intent about the future we hope to create. It is an imagining wherein all humans live in balance with our finite environment, where local communities thrive, diversity is embraced, and the world is a beautiful green utopia.

In this sense, Solarpunk is a hopeful reaction against the grim narratives of dystopian tales. In the same way that Noblebright was a reaction against Grimdark, Solarpunk is a reaction against Cyberpunk, or more broadly, Dystopian fiction.

As I’ve suggested before, dystopian conceits aren’t always bad; in fact in some way, they may envision a biblical worldview. In my piece, Christian Worldview and Dystopia I wrote:

…our inclination to envision a dystopian future has roots in a very biblical worldview.

The Bible does not paint a rosy picture about the fate of mankind. Whether it’s Jesus warning about natural and cosmological catastrophes, plagues, and times of great deception, or the apostle John’s hellacious account of the end of the age, Scripture paints a picture of things getting worse before they get better. Apparently, all our peace accords, technological advances, and therapeutic skills still land us in Armageddon. Far from Shangri la, we end up in an arena, pitted against God, nature and, each other. No amount of firepower or psychobabble can stave of these approaching hoofbeats.

The genre of dystopian books and films reinforces a vital biblical theme — Man is broken. No amount of moral or technological “tweaks” can correct the malfunction that is Us.

If this is true, it presents problems for the Solarpunk genre… from a biblical perspective. While a “green utopia” would seem to be a noble biblical goal, it’s the machinations of how we get there that’s the problem.

In his essay, On the Political Dimensions of Solarpunk, Andrew Dana Hudson writes,

Whatever solarpunk is, it is deeply political. Politics is the practice of determining the arrangements through which we distribute resources and otherwise relate to each other. In other words, who makes the stuff, who gets the stuff, and how we are expected to treat both people and stuff.

Nearly every piece of solarpunk content I’ve seen or read suggests that the solarpunk future is a result of nuanced choices about such arrangements, not wild technological advancements. The very name “solarpunk” implies that scientific breakthroughs alone won’t fix our environmental, social and economic problems. After all, it posits a world of solar-energy abundance and then argues that we will still have need of punks. No magical tech fixes for us. We’ll have to do it the hard way: with politics.

If you smell a rat in Hudson’s conclusion, it’s because there is one. Apparently, the implementation of a Solarpunk society reads something like a Green New Deal, one in which “we distribute resources” and reconfigure thinking as to “how we are expected to treat both people and stuff. “

If this sounds dangerously close to a sort of “eco-communism,” you’d be correct.

In Solarpunk is Not Your Political Agenda, the author anticipates some making the connection between Solarpunk and communism. In an appeal to the Solarpunk community, the author cautions against using communist language and symbols to represent the genre, especially in its early stage, but rather to keep that political debate for “back stage.”

If solarpunk is about including everyone on the Earth in a positive, optimistic future where we work together to focus on saving the planet, then let’s focus on saving the planet right now in our visuals, and save the political debate for “back stage”

In the comments, we argued how this would be enabling capitalism’s continued corruption, but I argued how, given that communism is still technically illegal to practice in the US (for example), using symbols that represent it so blatantly on our art could turn huge portions of the population off before Solarpunk even has a chance to take off as a “for-everyone” future.

And that’s the beauty: Communism, Socialism, Capitalism, Anarchy and probably every type of -ism will still exist in a solar punk future. There’ll probably even be rebels that drive gas vehicles just out of protest. That’s the beauty of keeping the ideological “image” of Solarpunk wide-open. So people who want other ideologies in their solarpunk future will not feel excluded, looking at art like what’s below and thinking they’re not meant for Solarpunk because they’re not X, Y or Z.

While extending the possibility of peaceful coexistence between communists, socialists, capitalists, and anarchists may make for good fiction, it’s little more than a mirage. History has proven that some ideologies cannot coexist.

In this, Hudson’s conclusion hews much closer to the social and political ramifications of this green utopia:

A solarpunk culture would strive to dissolve every form of social hierarchy and domination – whether based on class, race, gender, sexuality, ability, or species – dispersing the power some individuals or groups wield over others and thus increasing the aggregate freedom of all; empowering the disempowered and including the excluded. It is rooted in the legacy of such liberatory movements as anti-authoritarian socialism, feminism, racial justice, queer and trans liberation, disability struggles, animal liberation, and digital freedom projects.

Dissolving “every form of social hierarchy and domination – whether based on class, race, gender, sexuality, ability, or species” is a lofty goal. But how does one enforce “the aggregate freedom of all”? Who decides what power needs “dispersed”? And how does a society enforce the abolition of money, racism, homophobia, capitalism, or private property without violence? But without such enforcement, a Solarpunk future is utopian fiction.

Unless, of course, something like a Solarpunk KGB was created. And maybe Solarpunk workcamps, Solarpunk sensitivity training, and Solarpunk re-education centers. Come to think of it, maybe I’ve discovered a new subgenre — the Solarpunk Resistance.

Fits right along with the proposed “Green New Deal” put forward by a legislator who identifies herself as a Democratic Socialist. Or was that Socialist Democrat? I don’t remember. But either way, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) figures we can change all of society in 10 years. Because climate change is only one of the components the GND addresses. The other is economic inequity. Interesting how the two are linked.

Becky

I haven’t even seen any books in this genre, but then, I’m not woke. Sounds like they need some blockbuster authors to toe their line. Unless the book winds up like Mortal Engines, I doubt I’d be interested.